Guitar-driven blues sound? Is it John Mayer? Nope!

The songs aren't in English. Bad Bunny? Wrong again!

Their songs have a political slant. Rage Against The Machine? Incorrect!

They're actual political dissidents, living and recording in exile. Pussy Riot? Getting closer, but no!

With a resume like that, you would think that Tinariwen would be a household name. The story of their band reads like it's literally out of a movie, even starting with a four year old kid making his first guitar out of a plastic water can, a stick, and some string. This, of course, was after witnessing the execution of his father.

I didn't say it was a happy movie.

As I settled in to the sold out show at Chicago's Old Town School of Folk Music, I didn't really know what to expect from a band that could not be more different than myself if they tried. What I did know was that I was going to find out with one of the most diverse crowds I've ever seen at any live musical performance. Not just racially, but age-wise as well - I saw a kid who looked to be as young as about 8 years old just rows away from a couple that both looked to be pushing 75+. For that kind of crowd to gather on a Saturday night, this really had to be something special.

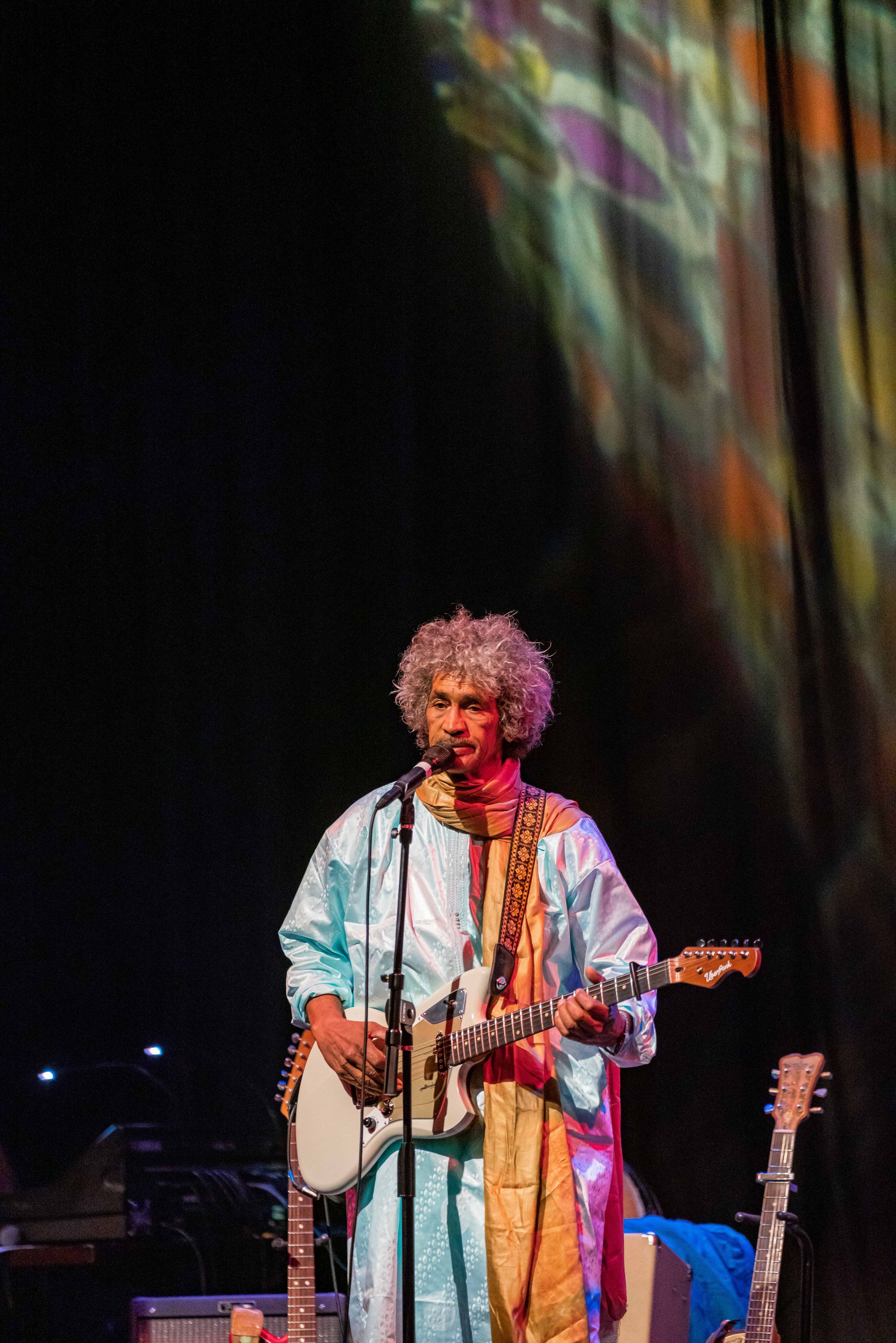

Pioneering a sound referred to as 'desert blues', the group gained word-of-mouth notoriety combining the sounds of traditional Tuareg and African guitar with the blues-rock sounds of bootlegged albums that made their way across the ocean during that time (Dire Straits, Santana, Jimi Hendrix). The resulting sound has propelled the group through 5 decades of recording, countless awards, and fans ranging from Robert Plant and Bono to Thom Yorke and Henry Rollins.

Encountering that kind of experience in the wild is always the best kind of surprise, and one that can leave you challenged to describe what it was you just went through, something I'm very much feeling right now as I type these words.

The reason I wanted to touch on the journey that Tinariwen has taken as a group is because that entire journey, all the hardships and the revolutions and the danger and political discourse...you feel it all in every one of their songs. I didn't have to share a language with the men in this group to know what they were singing about, what they were feeling as they performed. Very much pioneers of a subgenre of blues music, even their more uptempo and seemingly jubilant songs still had a hint of pain behind them, like a constant reminder that each freedom won had a price that had to be paid. That didn't stop audience members from literally dancing up and down the aisles from the first song through the last, constant exclamation points as a reminder that no matter how much pain and conflict driving it, there's always something joyous about performing music in front of others. And as long as there are willing conduits to turn those feelings into words and notes and verses, audiences of all ages and backgrounds will be able to come together and celebrate that music and hopefully spin something positive out of the negative.